Research

Enhancing Cybersecurity Resilience in Energy Infrastructure

Spatio Temporal Prediction and Coordination of EV Charging Demand for Power System Resilience

This project explores how the growing demand for electric vehicle charging affects the stability and resilience of today’s power systems. Our goal is to understand how charging behavior evolves across the grid and to build tools that help operators stay ahead of potential stress points as electric vehicle adoption continues to rise.

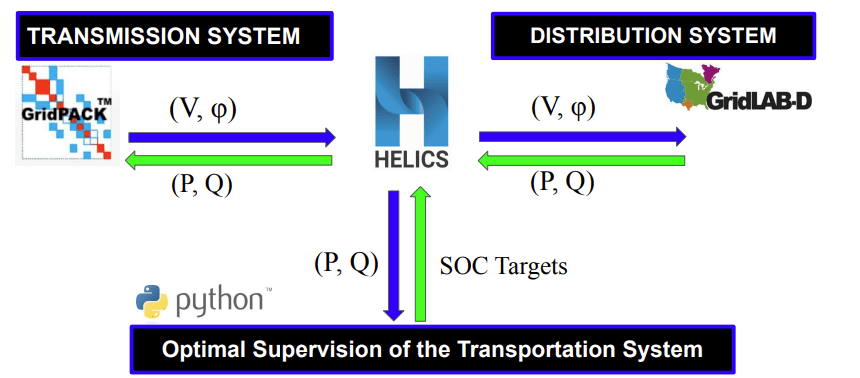

To do this, we created a spatio temporal prediction and coordination framework that brings together multiple modeling tools into one co-simulation environment. GridPACK is used to represent transmission system behavior, GridLAB-D captures distribution level effects, and HELICS synchronizes data across these models so we can observe real-time interactions between voltage, power flow, and battery state of charge. A Python-based supervisory controller then uses this information to schedule and coordinate charging activity, helping the system anticipate demand, prevent overloads, and maintain reliable operation.

Fig.1: System Architecture

Hidden Attribute Vulnerabilities in Smart Home IoT

This project investigates a newly uncovered vulnerability in smart home Internet of Things platforms called hidden attributes, which are device parameters accessible through Internet of Things application programming interfaces but invisible to users. These hidden attributes allow attackers to change device behavior in unexpected ways, creating significant security and safety risks. Our work systematically discovers these attributes across commodity devices, demonstrates practical attacks on major platforms such as Samsung SmartThings and Amazon Alexa, and develops automated tools to patch vulnerable edge drivers and strengthen smart home security.

https://xueningxu.github.io/xueningxu-profile/assets/hiddenAttribute.pdf

Exploring Malware Attacks in the Power Grid

This project explores how advanced industrial control system malware can disrupt the operation of modern power grids. Our goal is to understand how threats like Industroyer interact with real communication protocols and grid control logic, and to build a realistic environment where these attacks can be studied safely and accurately.

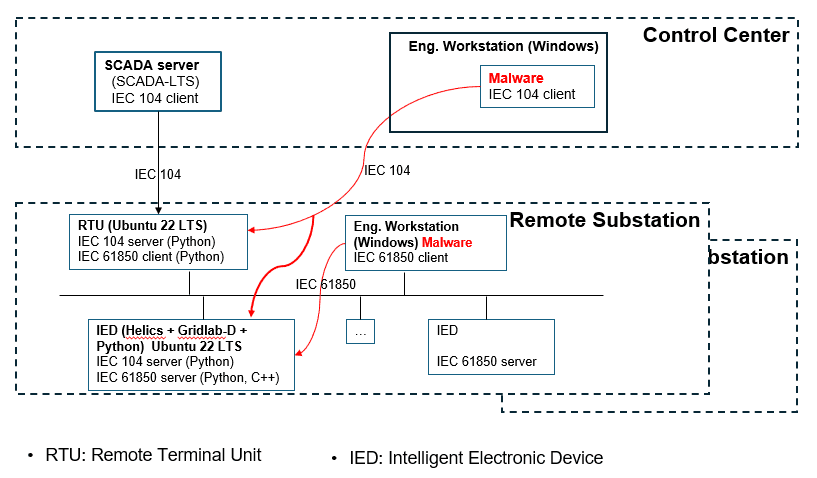

To support this work, we created a full testbed that brings together GridLAB D for distribution system simulation, a custom-built IEC 104 server for remote terminal unit behavior, and additional components modeled through the HELICS co-simulation framework. We adapted real Industroyer malware samples to run inside a virtual machine-based engineering workstation, allowing us to examine how malicious IEC 104 payloads manipulate switch states, breaker positions, and other critical controls across an emulated power distribution network.

By placing live malware “in the loop,” the testbed lets us observe how compromised engineering workstations communicate with substations, how packets propagate across control networks, and how physical infrastructure responds when commands are spoofed or altered. This research helps reveal how sophisticated ICS malware operates in practice and provides a foundation for designing stronger protections for critical grid infrastructure.

An integrated co simulation testbed combining GridLAB D, an IEC 104 server, Python based control logic, and a Windows engineering workstation running malware. This environment models realistic interactions between control center components, substations, and spoofed industrial control protocol traffic.

Fig. 2: Power Grid Malware Testbed Architecture

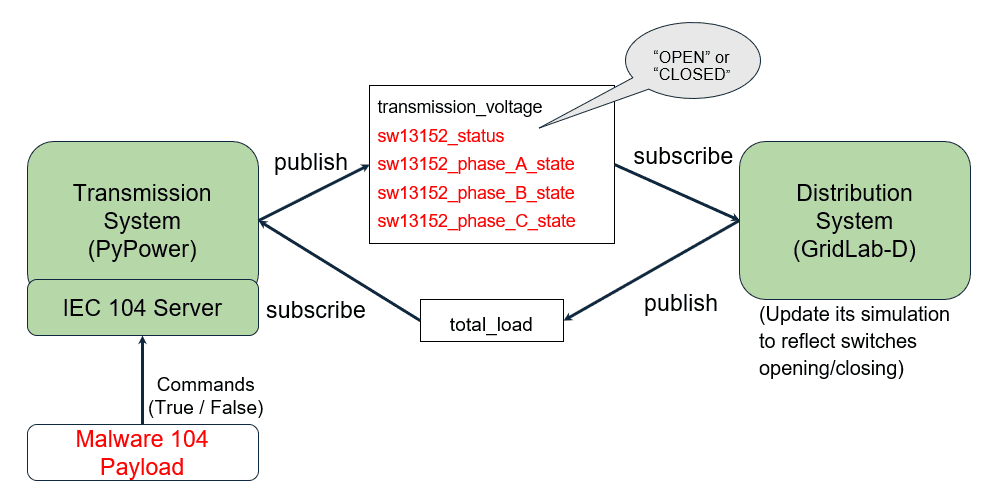

Fig. 3: Adding Malware into the Control Loop

Illustration of how Industroyer malware injects IEC 104 payloads into the system, modifies switch states, and influences real-time simulation values such as voltage, load, and breaker status.

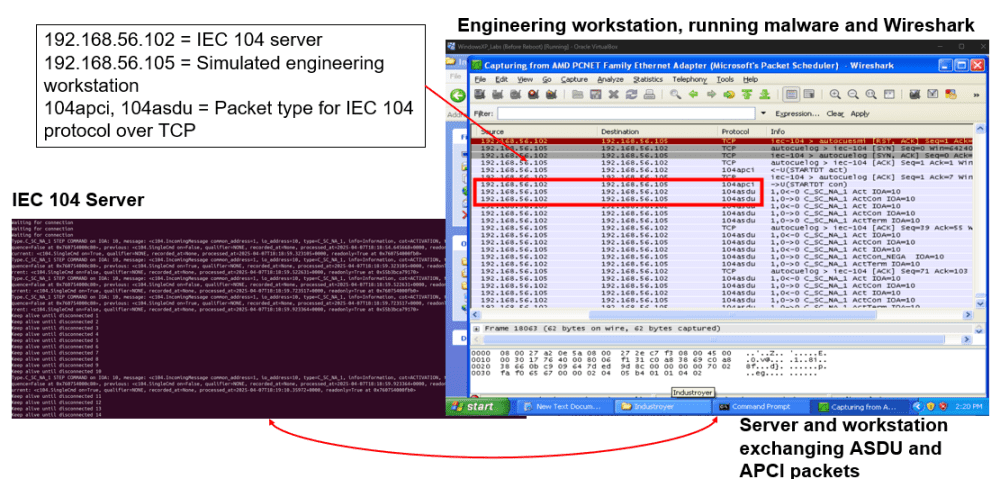

Fig. 4: Malware Interaction with IEC 104 Protocol

Packet level view of the engineering workstation and IEC 104 server exchanging APCI and ASDU messages, showing how the malware formats and issues unauthorized control commands.

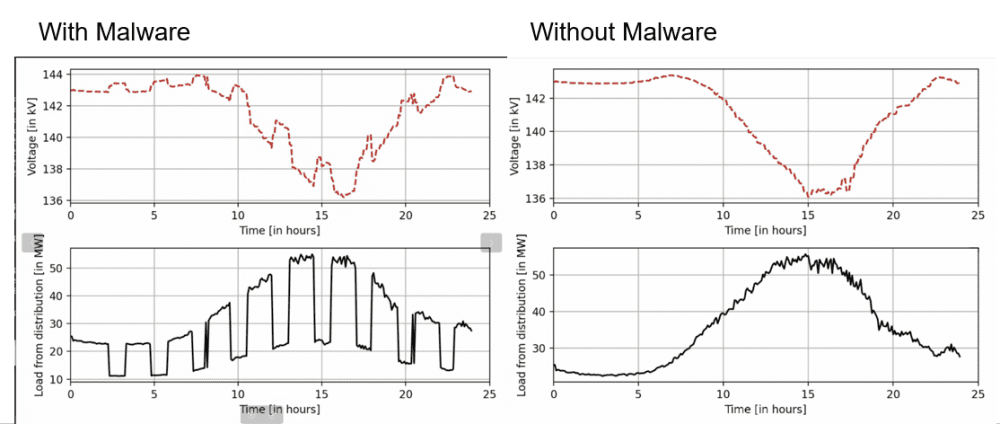

Fig. 5: Impact of Malware on Grid Behavior

Comparison of system behavior with and without malware. The malicious IEC 104 payload forces incorrect switch operations, creating amplified load conditions and potential instability.

Preliminary Experiments

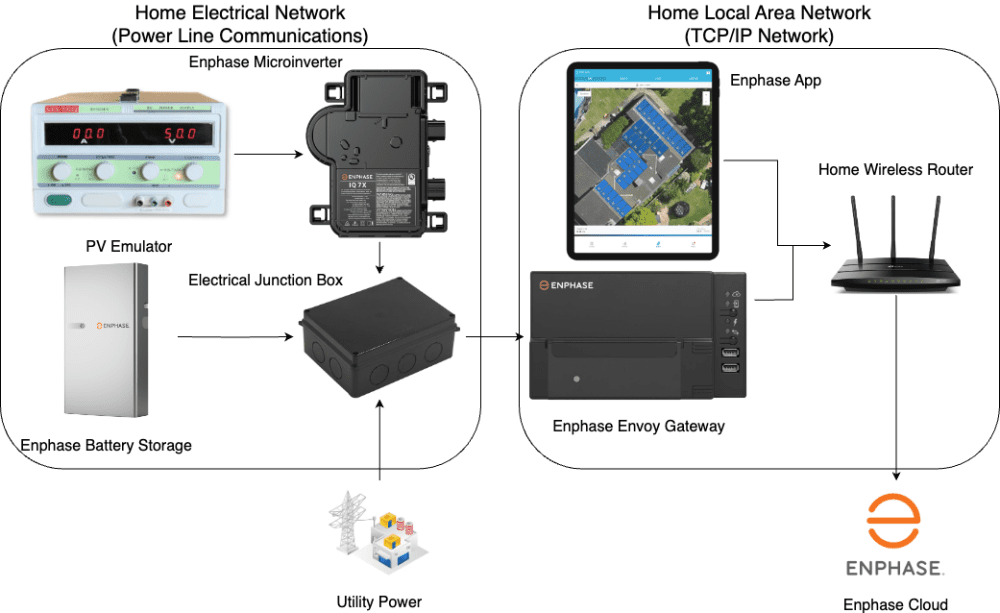

A second HIL lab setup, shown in Fig.1, contains an electrical network simulating a home solar power setup and allows for expansion to include devices such as but not limited to Electrical Vehicle Supply Equipment and battery storage. There is also a Home Local Area Network that allows for expansion to include other home and cloud connected devices. A Photovoltaic (PV) Emulator simulates a working solar panel, generating direct current (DC) electricity. A solar power microinverter converts DC power from the emulator to alternating current (AC) power compatible with the power grid. A solar power gateway controller monitors and manages the flow of solar power. Battery storage allows for the smart home to store and release energy for complete energy independence. The mobile app provides a comprehensive interface for monitoring and managing the solar power system. A solar power cloud serves as the centralized platform for data processing and storage. The electrical junction box acts as a central hub for wiring connections within the home solar power setup. The HIL setup is placed in the Flex Lab in EPIC, and it is connected to the grid emulator in the Smart Grid Lab in EPIC.

Fig.6: HIL Testbed with a Home Solar System in a Micro Smart Home

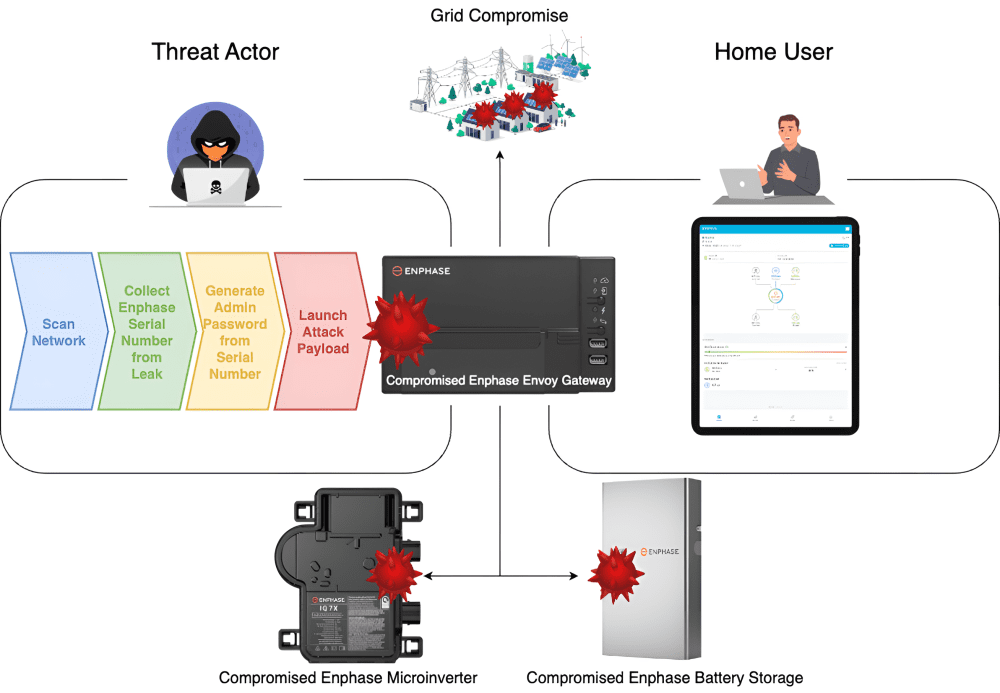

We conducted several preliminary cybersecurity experiments using the HIL testbed. We show the steps involved in the attack in blue, green, yellow and pink in the figure. Additionally, we were also able to identify several other vulnerabilities in the system targeting the solar power gateway controller, outlined below:

Fig.7: Privilege Escalation Attack

Hard-coded credentials: The default administrator password is the last 6 digits of the device’s serial number. The serial number is easily accessible from being physically printed on the device and can be remotely accessed from the status page. This vulnerability allows attackers with physical or remote access to gain administrative control.

• Predictable Solar Power Installer Password: The device generates a unique installer password with elevated privileges using a hash of the entire 12-digit serial number. Knowing the entire serial number allows attackers to predict the installer password, enabling unauthorized configuration changes to the solar power setup.

• Brute force: The solar power gateway controller allows for unlimited attempts to attempt to use trial and error to guess passwords.

• Denial-of-Service (DoS) Attack: Solar power gateway controllers often include APIs for polling real time energy production data. These APIs can be susceptible to denial-of-service attacks where the threat actor floods the device with illegitimate requests overwhelming its resources. Most Internet of Things devices lack the processing power and features to defend against Denial-of-Service attacks effectively. Our tests demonstrated that launching as few as 17 concurrent connections saturated the web server within the device, requiring a system reboot to restore functionality. The home user may not be able to access the device until it is reset.

• Replay Attack: This vulnerability allows attackers to intercept and replay valid data transmissions to manipulate the system. The solar power gateway controller lacks Secure Socket Layer (SSL) encryption, transmitting data unencrypted. We successfully intercepted and replayed a packet that can be used to start and stop power generation, demonstrating the potential safety risk for personnel working on a remotely controlled system under attacker control. Replayed commands could potentially damage grid infrastructure or other connected equipment.

By emulating a threat actor’s approach, we were able to identify potential vulnerabilities and explore the feasibility of gaining unauthorized access to an grid connected IoT device within the system. Once a threat actor has gained sufficient privileges within a system, an attack payload may be created that could lead to an attack on a power grid. This will allow us to analyze the broader electrical disruptions a threat actor could potentially orchestrate by compromising one or multiple smart homes within a larger system.